Interview: Lil Ya

12/13/2019

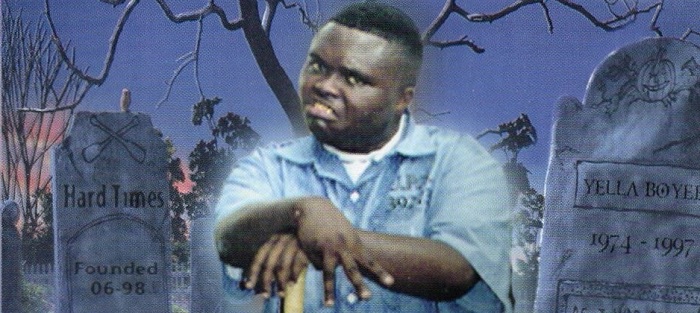

Lil Ya is a rapper from Third Ward, New Orleans. He’s best known as a member of U.N.L.V. (along with Tec-9 and Yella Boy), as well as for his 2000 solo record Another Massacre.

What was your relationship to music growing up?

I was dealing with music my whole life, from the church to school bands. I played in the marching band, but I learned to play a drum set when I took percussion lessons. I learned how to read music and stuff in the band. At that time, we didn’t have hip-hop or bounce music or anything like that. A lot of folks’ families, you was just raised in the house with blues and jazz music and stuff like that playin’. So you adapted to that before the hip-hop came to New Orleans.

At what point did you switch over to rapping?

I was actually in seventh grade. My uncle went to New York, and he came back and was tellin’ us about rap music, how big it was out there. The Fat Boys, all that kind of stuff. I wanted to be a singer; I knew I was gonna be dealing with music some kind of way, but I never could sing to be honest with you. So when he introduced me to rap, I was like “man, I could put words together and not have to sing! My Uncle Hardy, you probably heard his name in a few of our songs, we showed him love with both the logo and name of my label Hard Times Records. He went in with me to start the label, and I just wanted to show him a little love. He’d been doin’ time - actually, he’s right back in the penitentiary right now, he’ll be home in February - but he’d been doin’ hard time all this life. So we decided to call it that.

Me and Tec[-9] went to the same junior high school, so we formed a group with my little sister. She was like three years old at the time. And we started making positive raps, gettin’ in talent shows. And we won every talent show in the city, from the seventh grade to the eleventh grade. By the time the twelfth grade came, me and Tec was seventeen at the time, so we started sneakin’ in the clubs that you had to be twenty-one to get in. By that time, people like Gregory D and DJ Jimi was out there cutting records and stuff like that. So we’d go in the ballrooms and ask the DJs to let us see they microphones and put on a “Brown Beats or “Triggerman beat. We wasn’t rappin’ positive no more, because it seemed like nobody wanted to hear it in the clubs.

In New Orleans, nobody really wanted to hear deep subjects. Everybody wanted to hear the bounce music. For some strange reason, women just loved to be degraded out there. They loved when you called ‘em hoes and bitches, stuff like that. That’s the type of music they wanted to listen to at that time. Like I said, hip-hop didn’t really get to New Orleans until late, and when it did get there bounce was takin’ over. They wasn’t really ready for the positive messages in a lot of different rap songs that you would hear from New York.

Who had you modeled yourself after when you were starting to rap?

We wasn’t modelling ourselves after anyone when we first came out, but we did idolize N.W.A. Of course, the West Coast came a few years later, once we got like seventeen and started doin’ our thing. What we did was, we took that method of gangsta music and put it over bounce beats. That’s what distinguished us from a lot of other rappers in New Orleans; we wasn’t doing the mainly repetitious type rapping, saying the same things over in a bounce rap. We would put the gangsta lyrics over the bounce beats, and people loved it.

What’d you and Tec get up to as kids? Did you only come together for the music stuff, or before that?

Well we was best friends, and a lot of people actually think that we’re brothers because that’s how we hung. During the midst of hangin’, we both was musically-inclined, our backgrounds are almost the exact same. So that’s what we used to do a lot, besides the regular things little bad kids’ll do. We would get together and write raps, sing raps together and create ‘em together. Tec played the xylophones and also bass drum, and he had a voice. He can sing his ass off. He’s one of the first rappers to intertwine singing in his raps - you’ll hear him sing a few bars, then start back rappin’ or whatever.

Yella Boy didn’t come into the picture until a while later, right?

Yella Boy didn’t join the group until after we signed the deal with Cash Money and was workin’ on our album. He always hung with us, he was a good friend of ours, but he used to dance a lot. When we was doin’ the rappin’, he was dancing and stuff. So he decided that he really wanted to start rapping with us. Tec influenced me to add him to the group; I was totally against it at first. About the time we came out with 6th & Baronne, he was ready. We gave him a shot with “Eddie Bow.

What had made y’all choose the acronym “U.N.L.V.? Just watching March Madness?

Well, UNLV school was the shit at the time! But actually, I have a friend named Damian, and Damian and his friends went to a catholic school. They used to call themselves U.N.L.V., and they called it Uptown N****s Livin’ Violent. They never rapped or whatever, they just used that name for they crew. And I told them, once we started doin’ our thing in the clubs and didn’t want to go by Sporty MCs anymore, I told ‘em I was gonna take that and use it for the rap group. He’s also a rapper, his name is DH the Great now, and he was on my solo album Another Massacre. I give him all props for actually creatin’ U.N.L.V., the name.

Back in ‘92, ‘93, what was the reputation of Baby and Slim? Were they well-known around your area?

They had reputations as d boys; their brother was a big timer, had a lot of money. He was from Uptown, from the Thirteenth Ward, maybe two miles from the Third Ward where we from. We had heard of ‘em and whatever, but it’s crazy because when I brought him home to meet my mom my sister knew him! My sister was like “what you doin’ in here? She was surprised, because she knew him from junior high school - Baby was like a superstar in sports, everybody knew him from playing sports in school. She couldn’t believe that that was what he was doin’, he really wasn’t a street guy at the time. During that time, everyone knew him as a quiet, good schoolboy.

Was that pretty standard, people taking street money and trying to turn it legitimate with a label?

Yeah, at least 85% of the record labels started like that. They took the street money and wanted to do something positive with it. Nowadays, they doin’ stuff like starting car washes and barber shops, but back then rap was poppin’ off in New Orleans.

What kind of studio setup did you have for those early tapes?

Our first single, “Another Bitch, we recorded - this was before we met Baby and them - we recorded it at my friend T-Bone’s house. Baby and them got ahold of the tape, and once we got with them we were actually recording in Mannie Fresh’s kitchen. That generated money for them to put people that came after us like Lil Slim, Pimp Daddy in the studio. But we recorded our whole first album in Mannie Fresh’s kitchen, sittin’ on crates holding a microphone with a wire on it.

He was a good bit older than y’all, right? Were you able to get along well enough?

We got along like family, man. We didn’t really start having fallouts with Baby and Slim until maybe… ‘96. Our last album, Uptown 4 Life, that’s when we started thinking hey man, we wanna have our own one day. We learned a lot from ‘em and thanked ‘em for it, but the goal was to have our own company. We didn’t wanna be under them forever.

Do you have any sense of how Baby got ahold of your record initially?

We started dubbin’ it on tapes, and we was sellin’ our tapes for five dollars, just me and Tec. He’d take a night dubbing the tapes, then we’d go out the next day and sell all those, then I’d take a turn. That process went on probably two, three months. The tape got into Baby’s hands, and he told a guy that we went to school with that he wanted a meeting with us to offer up a contract. He already had our music, asked if we had more songs ready. That’s when Mannie Fresh came into the picture; he was like “well we got a producer, y’all won’t be needin’ T-Bone no more. We was upset about that at first, but when we found out that Mannie Fresh was the same guy who’d had the record deal with Gregory D before, we was happy about it. We tried to bring T-Bone along with us, but it was Baby’s decision, not ours.

Were you putting any kind of contact info on the tapes, or was it all this kind of situation where everybody knew somebody who knew somebody else?

That’s exactly how it was. New Orleans is so small that everybody knows somebody who knows that person. We didn’t have a number on the tape or none of that, he just ended up knowin’ T-Bone’s friend Kevin. He let us know, and we went to the office. While goin’ in the office, they was actually goin’ in at the same time. We got in an elevator with those guys and we didn’t know who they was, they didn’t know who we were! And once we got on the floor, we went opposite ways - they went left, we went right. Once we’re lookin’ for the address on the doors, we didn’t see it so we ended up going back down the way they went. We saw the Cash Money sign, knocked on the door, and the same guys answer the door. They was like “man, didn’t y’all just get out the elevator? But that’s how we met ‘em.

Did getting on the label lead to any kind of touring or concerts or anything, or were you still just showing up at club nights?

We was excited, so of course we was tellin’ everybody - we got a record deal, we got a record deal! But we was still goin’ to the clubs, doin’ our thing and helping ourselves get the buzz that we wanted. Later on, they started booking shows for us at different clubs outside of New Orleans. And also in New Orleans, at The Big Easy with Bobby Marchan. We continued to do our thing, but we couldn’t as much because they had us on the road too. You didn’t really have rappers in Baton Rouge playing shows in Baton Rouge until the mid-’90s; in the early ‘90s and late ‘80s, everyone was comin’ from New Orleans. And we didn’t really go outside the state doin’ shows, it was only in Louisiana. We migrated in the late ‘90s, and then we started going to Houston. Texas was the first state outside of Louisiana that we started doing shows in.

How did those shows elsewhere in the state differ from the ones back home?

They were bigger, and it was a more… New Orleans shows was more of a intimate crowd. You didn’t even have a stage, we used to perform on the floor. People was more close to you and stuff like that. Versus going to Lafayette, we would go to like Strawberries in Lafayette and it’s a big ol’ stage and a more real type setting.

Was everything in New Orleans one big scene, or was it kind of like people sticking with whoever was right there in their neighborhood?

We were from the Third Ward, we represented that everywhere we went, but it was never just a Third Ward crowd there. If we have a show in the Third Ward, we gettin’ downtown people, we gettin’ Seventh Ward, Ninth Ward. People would come from all over to see us. It was unified - it wasn’t always a nice crowd, meaning it wasn’t beef. You know how New Orleans is with the wards, if you from Downtown and you get caught Uptown, you can get killed. And a lot of times the crowd had fights or whatever, but we would do our thing and be received with open arms.

How did you end up finding Juvenile and B.G.?

Yeah, actually I met B.G. when he was a little baby. He was like three years old, he stayed in our hood. He stayed on Yella block, matter of fact. When we was small, Yella was pushin’ B.G. on a Big Wheel - me and Yella had to be seven or eight, B.G. was like two or three - and the Big Wheel flipped over and messed B.G. jaw up. Later on, B.G. was eleven or twelve and he moved to Baby’s neighborhood. We didn’t find out that it was the same little dude until once he got signed, almost - his mom always remembered me, she’s like family with my family, and she didn’t want B.G. to sign with Baby and them because they was known dope boys. But I told her nah, they don’t do that no more, they doin’ this and that, and I helped him get signed.

Another interesting story was with Juvenile, he had a record out before we did because he was runnin’ with DJ Jimi. He had fell off, I don’t know what happened, but he stopped makin’ music. I saw him at the bus stop on my way to the studio to work on B.G.’s It's All On U Vol. 2 album, so we chatted a minute. I told him man, if you still rap I’ll bring you to the studio with me right now. He got in my van and we went to the studio, where I told him to rap for Baby and them. Baby knew of him, whatever, but they wasn’t interested in him or nothin’ like that. So once they heard him rap, they was like “yeah, man, we got somethin’ right here!

Pimp Daddy was another guy I helped get signed, he was with Full Pack at the time but he always wanted to be down with us. That was our dude - he wasn’t from the Third Ward, but he used to hang in the clubs that we would rap in. He used to get on the mic sometimes, but when he came out with that song “Got To Be Real that attracted Cash Money. Baby just asked him to help him go through a couple things and take it to the lawyer to get him out his contract if he was interested in signing.

Did you like doing that A&R type stuff, or would you rather have just been making music?

I liked it, I always was the type of person that loved to see somebody do what they loved doin’, being where they wanna be with it.

How did you change up your approach for Another Massacre as opposed to writing for U.N.L.V. records or with Cash Money in mind?

Pretty much, I understood after the Mannie Fresh era that a name didn’t make a good producer. You have cats that’s never been heard that can make some nice tracks. If I’m in that position, I always wanna give a person an opportunity. The chemistry that me and Tec had - I might feel a track and he don’t feel it or vice versa, and we just have to leave that alone. We both have to be feeling that track that we workin’ with. It was definitely different; with another person workin’ with you, it’s like “I’m feelin’ it, he feelin’ it, it’s a go! But if you the only one listenin’ to something and you don’t have somebody to amen to it, you like “maybe this ain’t the track.

I hadn’t saw a lot of different stuff back then. I actually recorded more than half of Another Massacre in San Antonio; a guy named Ricé actually did half the tracks on that album. It was just different, I wasn’t on the block all day. 6th & Baronne days, we’d be in the same spot all day pretty much. Sun up, sun down. So I had a lot more to talk about. And you don’t know if people are gonna accept that or not. But I think if you givin’ ‘em that same flavor, even if your story’s a little different, they gonna accept it.